There have been many famous First Pets. Fala. Checkers. Socks the Cat. Abraham Lincoln had a pet turkey. The Theodore Roosevelts had a badger. Many presidents kept cows at the White House. My personal favorite: Old Ike, Woodrow Wilson’s tobacco-chewing ram. If you are curious about presidential pets, visit the virtual presidential pet museum here.

But when it comes to dogs, there’s one president who runs ahead of the pack — George Washington. In honor of his birthday just passed, I thought it would be fun to take a look at Washington’s relationship with dogs and learn more about how America’s most popular household pet lived in the late Colonial and Revolutionary eras. (I cannot tell a lie… According to the AVMA, there are more pet cats than dogs in the US, but there are more households that own dogs than there are households that own cats. In short, cat-owners tend to own more than one cat, while most dog owners tend to stick with one dog.)

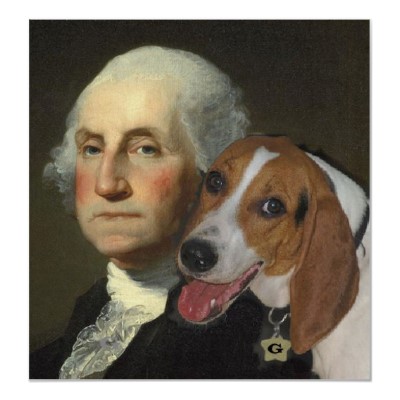

Most Americans know that George Washington was the “father of our country.” Fewer know that he was the father of the American Foxhound and that he once called a truce in mid-battle so that a wandering terrier could be safely returned to his owner, who just happened to be the opposing general. (Here are some books on this for young readers and for adults.) It’s estimated that he owned upwards of fifty dogs in his life, from household pets to his hunting pack. It brings us closer to him to know their names. There were Tippler, Truelove and Drunkard. Venus, Vulcan (a notorious ham-stealer) and Madame Moose, who was so frisky that Washington was obliged to buy her a mate. “A new coach dog for Madame Moose” had arrived, he recorded in his diary. “Her amorous fits should therefore be attended to.” And then there was Sweetlips, a “tall, exceedingly graceful dog of the hound type” who stayed with Washington in Philadelphia during his visit to the First Continental Congress and was spied by the Philadelphia mayor’s wife walking with his master down Walnut St. It’s an image of the bewigged, wooden-toothed man on the dollar that we didn’t get in grade school.

Washington wasn’t the only founding father to love dogs. Revolutionary war general Charles Lee— one of Washington’s staunchest critics within the Continental army— was generally surrounded by dogs and was so fond of his Pomeranian “Spado” that when the dog went missing, he advertised a $20 reward for his return in the Virginia Gazette. That’s a lot of money. (Click here to learn about the difficulties in calculating the value of colonial currency in terms that make sense today. But still, that was a lot of money.) Spado’s disappearance prompted Abigail Adams to write to her husband John: “I see by the papers you sent me that Spado is lost. I mourn for him…” (March 10, 1777).

It’s not easy to find out what the average dog ate and how he lived in Colonial times, though we can speculate about a dog’s life from letters, laws passed, wills and inventories, and visual evidence such as paintings. It’s clear that by the 18th century the dog’s reputation had risen remarkably. From being synonymous with a slur in Shakespeare’s time (“You dog! You cur!”) he had become Benjamin Franklin’s definition of one of three true friends. (The others were “an old wife” and “ready money.”) Dogs had especially come a long way in Washington’s home colony of Virginia, where they had been on the menu at Jamestown during the “starving time.” Dipping into Ivor Noel Hume’s classic Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America there’s no section on dogs (the horse and its equipment is the only animal with its own section) but in the section on toys there’s mention of “a beautifully modeled redware dog with an Elizabethan-style collar around its neck,” which seems a pet-like representation.

This artifact is in keeping with what was happening in visual art. The rising bourgeoisie within colonial cities and the land-holding class imitated their British counterparts by keeping dogs as pets, an indication of prosperity if not actual excess, and showed them off in paintings. Dogs appeared more and more along with their masters in painted portraits, on snuffboxes, decorative furbelows. Eventually, dog portraits became a genre of their own.

Not everyone— even in Virginia— sympathized with the proto-Garden and Gun crowd. Just as ranchers today deal with wolves, so 18th-century farmers had to deal with wild dogs, which they claimed were worse than wolves, and the losses they incurred. In 1772, the city of Williamsburg limited the number of dogs per household to two, and these two had to be collared with their owner’s initials. If not, and caught, they could be killed.

Has anyone written the story of dogs in the making of America? Or will dogs stay only in our hearts and out of the history books? Anyone who grew up like I did in Nashville or who has read Harriet Simpson Arnow’s Flowering on the Cumberland will remember how helpful dogs could be in what was then the wild west of the Revolutionary Era. What impact did their love for dogs have on the colonial society from which we sprang and how has it helped to make us who we are? I’d love to see some formal study. For now I’ll just quote Washington’s near contemporary, Voltaire: “The best thing about man is… the dog.”

I’m with Voltaire 🙂

LikeLike